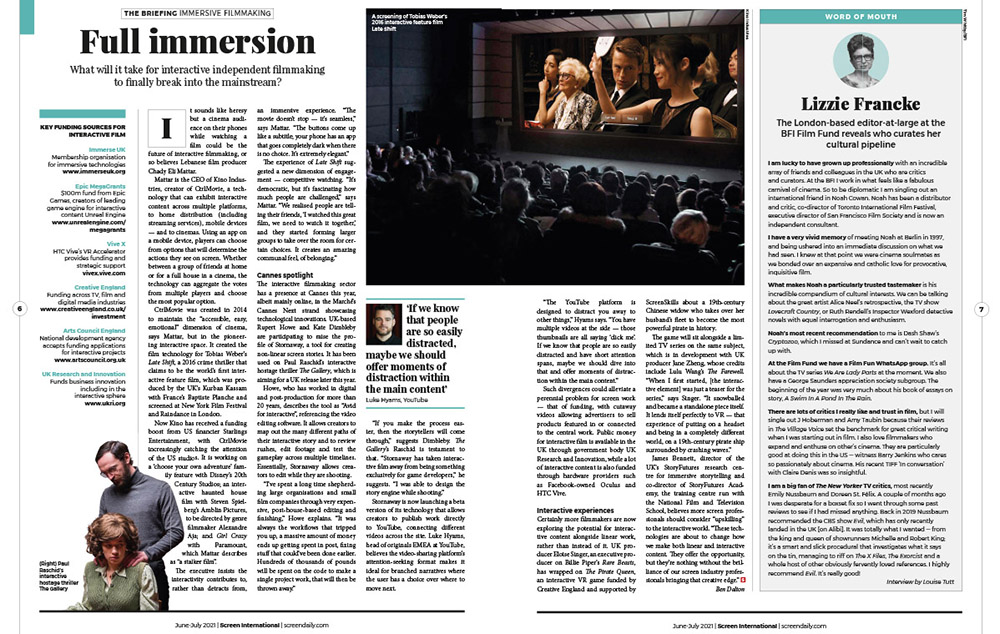

To coincide with our presentation at Cannes Marche Du Film this month, we were delighted to feature in this month’s Screen Daily article about the future of interactive filmmaking.

You can read the article below or online here

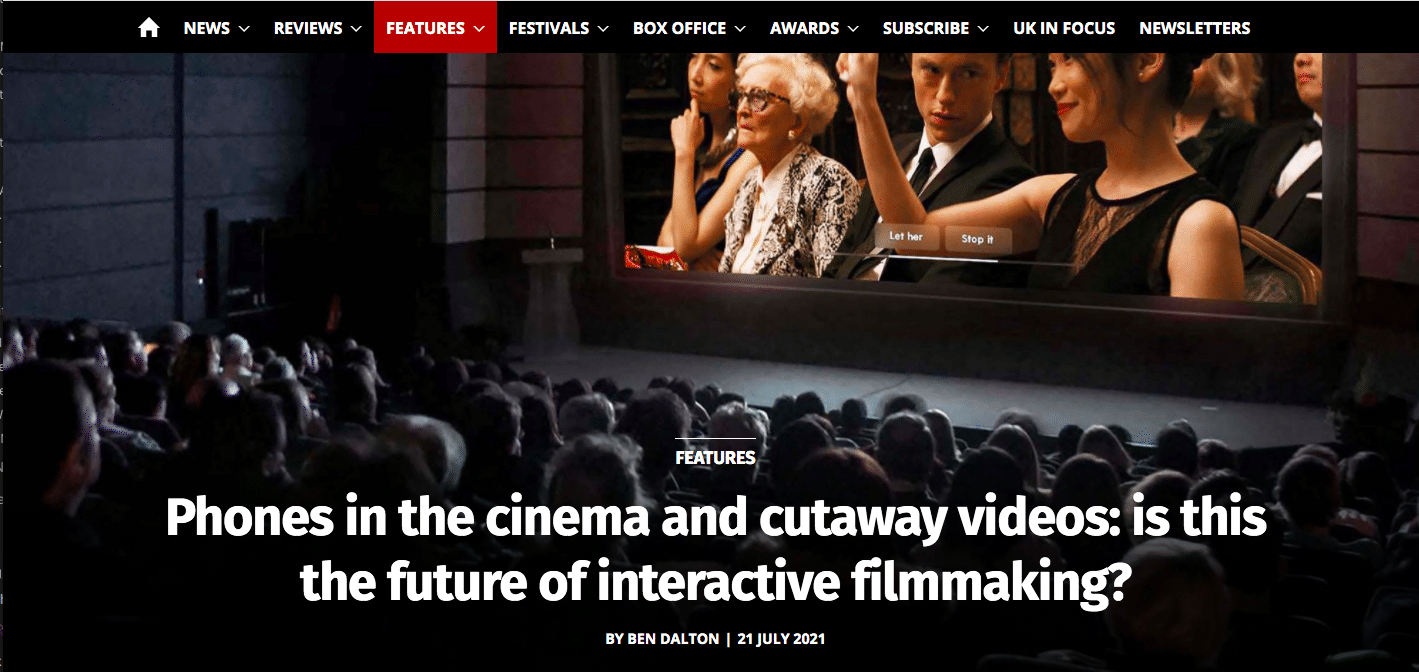

Phones in the cinema and cutaway videos: is this the future of interactive filmmaking?

Ben Dalton July 2021

It sounds like heresy but a cinema audience on their phones while watching a film could be the future of interactive filmmaking.

Or so believes Lebanese film producer Chady Eli Mattar. Mattar is the CEO of Kino Industries, creator of CtrlMovie, a technology that can exhibit interactive content across multiple platforms, to home distribution (including streaming services), mobile devices — and to cinemas. Using an app on a mobile device, players can choose from options that will determine the actions they see on screen. Whether between a group of friends at home or for a full house in a cinema, the technology can aggregate the votes from multiple players and choose the most popular option.

CtrlMovie was created in 2014 to maintain the “accessible, easy, emotional” dimension of cinema, says Mattar, but in the pioneering interactive space. It created the film technology for Tobias Weber’s Late Shift, a 2016 crime thriller that claims to be the world’s first interactive feature film, which was produced by the UK’s Kurban Kassam with France’s Baptiste Planche and screened at New York Film Festival and Raindance in London.

Now Kino has received a funding boost from US financier Starlings Entertainment, with CtrlMovie increasingly catching the attention of the US studios. It is working on a ‘choose your own adventure’ family feature with Disney’s 20th Century Studios; an interactive haunted house film with Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Pictures, to be directed by genre filmmaker Alexandre Aja; and Girl Crazy with Paramount, which Mattar describes as “a stalker film”.

The executive insists the interactivity contributes to, rather than detracts from, an immersive experience. “The movie doesn’t stop — it’s seamless,” says Mattar. “The buttons come up like a subtitle; your phone has an app that goes completely dark when there is no choice. It’s extremely elegant.”

The experience of Late Shift suggested a new dimension of engagement — competitive watching. “It’s democratic, but it’s fascinating how much people are challenged,” says Mattar. “We realised people are telling their friends, ‘I watched this great film, we need to watch it together,’ and they started forming larger groups to take over the room for certain choices. It creates an amazing communal feel, of belonging.”

Cannes spotlight

The interactive filmmaking sector had a presence at Cannes this year, albeit mainly online, in the Marché’s Cannes Next strand showcasing technological innovations. UK-based Rupert Howe and Kate Dimbleby participated to raise the profile of Stornaway, a tool for creating non-linear screen stories. It has been used on Paul Raschid’s interactive hostage thriller The Gallery, which is aiming for a UK release later this year.

‘THE GALLERY’

Howe, who has worked in digital and post-production for more than 20 years, describes the tool as “Avid for interactive”, referencing the video editing software. It allows creators to map out the many different paths of their interactive story and to review rushes, edit footage and test the gameplay across multiple timelines. Essentially, Stornaway allows creators to edit while they are shooting.

“I’ve spent a long time shepherding large organisations and small film companies through very expensive, post-house-based editing and finishing,” Howe explains. “It was always the workflows that tripped you up, a massive amount of money ends up getting spent in post, fixing stuff that could’ve been done earlier. Hundreds of thousands of pounds will be spent on the code to make a single project work, that will then be thrown away.”

“If you make the process easier, then the storytellers will come through,” suggests Dimbleby. The Gallery’s Raschid is testament to that. “Stornaway has taken interactive film away from being something exclusively for game developers,” he suggests. “I was able to design the story engine while shooting.”

Stornaway is now launching a beta version of its technology that allows creators to publish work directly to YouTube, connecting different videos across the site. Luke Hyams, head of originals EMEA at YouTube, believes the video-sharing platform’s attention-seeking format makes it ideal for branched narratives where the user has a choice over where to move next.

“The YouTube platform is designed to distract you away to other things,” Hyams says. “You have multiple videos at the side — those thumbnails are all saying ‘click me’. If we know that people are so easily distracted and have short attention spans, maybe we should dive into that and offer moments of distraction within the main content.”

Such divergences could alleviate a perennial problem for screen work — that of funding, with cutaway videos allowing advertisers to sell products featured in or connected to the central work. Public money for interactive film is available in the UK through government body UK Research and Innovation, while a lot of interactive content is also funded through hardware providers such as Facebook-owned Oculus and HTC Vive.

Interactive experiences

SOURCE: SINGER STUDIOS ‘THE PIRATE QUEEN’

Certainly more filmmakers are now exploring the potential for interactive content alongside linear work, rather than instead of it. UK producer Eloise Singer, an executive producer on Billie Piper’s Rare Beasts, has wrapped on The Pirate Queen, an interactive VR game funded by Creative England and supported by ScreenSkills about a 19th-century Chinese widow who takes over her husband’s fleet to become the most powerful pirate in history.

The game will sit alongside a limited TV series on the same subject, which is in development with Beijing-based producer Jane Zheng, whose credits include Lulu Wang’s The Farewell. “When I first started, [the interactive element] was just a teaser for the series,” says Singer. “It snowballed and became a standalone piece itself. It lends itself perfectly to VR — that experience of putting on a headset and being in a completely different world, on a 19th-century pirate ship surrounded by crashing waves.”

James Bennett, director of the UK’s StoryFutures research centre for immersive storytelling and co-director of StoryFutures Academy, the training centre run with the National Film and Television School, believes more screen professionals should consider “upskilling” to the interactive world. “These technologies are about to change how we make both linear and interactive content. They offer the opportunity, but they’re nothing without the brilliance of our screen industry professionals bringing that creative edge.”